South of Amman

Undoubtedly the most famous attraction in Jordan is the Nabatean city of Petra, nestled away in the mountains south of the Dead Sea. Petra, which means "stone" in Greek, is perhaps the most spectacular ancient city remaining in the modern world, and certainly a must-see for visitors to Jordan and the Middle East.The city was the capital of the Nabateans -Arabs who dominated the lands of Jordan during pre-Roman times- and they carved this wonderland of temples, tombs and elaborate buildings out of solid rock. The Victorian traveler and poet Dean Burgon gave Petra a description which holds to this day -"Match me such a marvel save in Eastern clime, a rose-red city half as old as time." Yet words can hardly do justice to the magnificence that is Petra. In order to best savor the atmosphere of this ancient wonder, visit in the quiet of the early morning or late afternoon when the sandstone rock glows red with quiet grandeur.

Petra in snow. © Jad Al Younis, Discovery Eco-Tourism

For seven centuries, Petra fell into the mists of legend, its existence a guarded secret known only to the local Bedouins and Arab tradesmen. Finally, in 1812, a young Swiss explorer and convert to Islam named Johann Ludwig Burckhardt heard locals speaking of a "lost city" hidden in the mountains of Wadi Mousa. In order to find the site without arousing local suspicions, Burckhardt disguised himself as a pilgrim seeking to make a sacrifice at the tomb of Aaron, a mission which would provide him a glimpse of the legendary city. He managed to bluff his way through successfully, and the secret of Petra was revealed to the modern Western world.Much of Petra’s fascination comes from its setting on the edge of Wadi Araba. The rugged sandstone hills form a deep canyon easily protected from all directions. The easiest access to Petra is through the Siq, a winding cleft in the rock that varies from between five to 200 meters wide. Petra’s excellent state of preservation can be attributed to the fact that almost all of its hundreds of "buildings" have been hewn out of solid rock: there are only a few free-standing buildings in the city. Until 1984, many of these caves were home to the local Bedouins. Out of concern for the monuments, however, the government outlawed this and relocated the Bedouins to housing near the adjacent town of Wadi Mousa.

Petra is located just outside the town of Wadi Mousa in southern Jordan. It is 260 kilometers from Amman via the Desert Highway and 280 kilometers via the King’s Highway. There are numerous and varied accommodations available in Wadi Mousa, as well as a few hotels on the panoramic drive between Wadi Mousa and the nearby (15 kilometers) village of Taybet. Camping is now illegal inside Petra.

History

HistoryThe area’s principle water source, Ain Mousa (Spring of Moses), is thought by some to be one of the many places where the Prophet Musa (Moses) struck a rock with his staff to extract water (Numbers 20: 10-13). Prophet Aaron, brother of Moses and Miriam, died in the Petra area and was buried atop Mount Hor, now known as Jabal Haroun (Mount Aaron).

Sometime during the sixth century BCE, a nomadic tribe known as the Nabateans migrated from western Arabia and settled in the area. It appears as though the Nabatean migration was gradual and there were few hostilities between them and the Edomites. As the Nabateans forsook their nomadic lifestyle and settled in Petra, they grew rich by levying taxes on travelers to ensure safe passage through their lands. The easily defensible valley city of Petra allowed the Nabateans to grow strong.

Petra. © Zohrab

From its origins as a fortress city, Petra became a wealthy commercial crossroads between the Arabian, Assyrian, Egyptian, Greek and Roman cultures. Control of this crucial trade route between the upland areas of Jordan, the Red Sea, Damascus and southern Arabia was the lifeblood of the Nabatean Empire and brought Petra its fortune. The riches the Nabateans accrued allowed them to carve monumental temples, tombs and administrative centers out of their valley stronghold.The Seleucid King Antigonus, who had come to power in Babylonia when Alexander the Great’s empire was divided, rode against the Nabateans in 312 BCE. The Nabateans eventually repelled the invaders, and records indicate that they were eager to remain on good terms with the Seleucids in order to perpetuate their trading ambitions. While the Seleucids could not conquer the Nabateans militarily, their Hellenistic culture made a lasting impact upon the Nabateans. New ideas in art and architecture influenced the Nabateans at the same time that their flourishing empire was expanding northward into Syria, around 150 BCE. The term "empire" is used loosely here, for it was more a zone of influence. As the Nabateans expanded northward, more caravan routes and, consequently, trading riches, came under their control. It was primarily this, rather than territorial acquisition or cultural domination, that motivated them.

The growing economic and political power of the Nabateans began to worry the Romans, and in 63 BCE Pompey dispatched a force to cripple Petra. Nabatean King Aretas III either defeated the Roman Legions or paid a tribute to keep peace with them. Later, the Nabateans made a mistake by siding with the Parthians in their war with the Romans. After the Parthians’ defeat, Petra had to pay tribute to Rome. When they fell behind in paying this tribute, they were invaded twice by the Roman vassal King Herod the Great. The second attack, in 31 BCE, saw him take control of a large swath of Nabatean territory, including the lucrative northern trading routes into Syria. With their trading empire reduced to a shell of its former glory, the Nabatean Empire staggered on for almost another century and a half. The last Nabatean monarch, Rabbel II, struck a deal with the Romans that as long as they did not attack during his lifetime, they would be allowed to move in after he died. Upon his death in 106 CE, the Romans claimed the Nabatean Kingdom and set about transforming it with the usual plan of a colonnaded street, baths, and the common trappings of modern Roman life.

Much of what is known about Nabatean culture comes from the writings of the Roman scholar Strabo. He recorded that their community was governed by a royal family, although a spirit of democracy prevailed. Strabo also notes the materialism of the Nabateans.

With its incorporation into the Roman Empire, Petra began to thrive once again. The city may have housed 20,000-30,000 people during its heyday. The fortunes of Petra began to decline with the shift in trade routes to Palmyra in Syria and the expansion of seaborne trade around Arabia. The city was struck another blow in 363 CE, when the free-standing structures of Petra were thrown to the ground in a violent earthquake. Fortunately, Petra’s greatest constructions were preserved, carved as they are into the rock faces.

It is not known whether the inhabitants of Petra left the city before or after the fourth century earthquake. The fact that very few silver coins or valuable possessions have been unearthed at Petra indicates, however, that the withdrawal was an unhurried and organized process. One theory holds that the city of Petra was primarily a religious and administrative center, used occasionally as a fortress during times of war. The preponderance of temples and tombs supports this theory, which holds that as the dead began to consume more and more of Petra’s space, the living relocated to other caves or tents outside the inner confines of the "holy" city.

It seems clear that by the time of the Muslim conquest in the seventh century CE, Petra had slipped into obscurity. The city was damaged again by the earthquake of 747 CE, and housed a small Crusader community during the 12th or 13th century. It then passed into obscurity and was forgotten until Johann Ludwig Burckhardt rediscovered it for the outside world in 1812.

Sights of Interest

Sights of InterestEven before you reach the Siq, you will notice three square free-standing tombs on your right. No evidence of bones has been found, but it may be that these are a type of tombstone. Further along on the left, built high into the cliff, stands the Obelisk Tomb, which once stood seven meters high. Five graves were found inside the tomb, four represented by pyramid-shaped pillars and the last by a statue between the middle pillars. Closer to the Siq, rock-cut channels once brought the waters of Ein Mousa through ceramic pipes to the inner city as well as to the surrounding farm country. When designing a new dam, excavators uncovered the Nabateans’ ancient dam and used it as a model for the modern one.

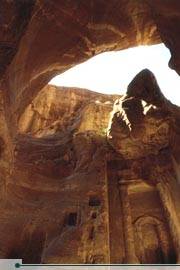

As you enter the Siq, the path narrows to about five meters and the walls tower over 200 meters overhead, casting enormous shadows on the niches that once held icons of the gods Dushara and al-Uzza. The icons were meant to protect the entrance and hex unwelcome visitors. The entrance to the Siq was once topped by a ceremonial arch built by the Nabateans. It survived until the late ninth century, and you can still see remains of it as you enter the gorge. The original channels cut in the walls to bring water into Petra can also be seen, and in some places the original terracotta pipes are still in place.

After winding around for 1.5 kilometers, the Siq suddenly opens upon the most impressive of all Petra’s monuments -al-Khazneh (Arabic for "the Treasury"

. One of the most elegant remains of antiquity, it is carved out of solid rock from the side of a mountain, and stands over 40 meters high. Although it served as a royal tomb, the Treasury gets its name from the legend that pirates hid their treasure there, in a giant stone urn which stands in the center of the second level. Believing the urn to be filled with ancient pharoanic treasures, the Bedouins periodically fired guns at it: proof of this can be seen in the bullet holes which are clearly visible on the urn. Much speculation has gone into the barely distinguishable reliefs which can be seen on the exterior of the Khazneh, although consensus is that they represent various gods. The Khazneh’s age has also been debated, with estimates ranging from 100 BCE to 200 CE.

. One of the most elegant remains of antiquity, it is carved out of solid rock from the side of a mountain, and stands over 40 meters high. Although it served as a royal tomb, the Treasury gets its name from the legend that pirates hid their treasure there, in a giant stone urn which stands in the center of the second level. Believing the urn to be filled with ancient pharoanic treasures, the Bedouins periodically fired guns at it: proof of this can be seen in the bullet holes which are clearly visible on the urn. Much speculation has gone into the barely distinguishable reliefs which can be seen on the exterior of the Khazneh, although consensus is that they represent various gods. The Khazneh’s age has also been debated, with estimates ranging from 100 BCE to 200 CE.

"Al-Khazneh", the Treasury, Petra. © Michelle Woodward

As the Siq turns right and leads down toward the city, the number of niches and tombs increases, becoming a virtual graveyard in rock arching around behind the 8000-seat Amphitheater. Originally thought to have been built by the Romans after their defeat of the Nabateans in 106 CE, it is now believed that the Nabateans cut the Amphitheater out of the rock around the time of Christ, slicing through many caves and tombs in the process. Under the stage floor were store rooms and a slot through which a curtain could be lowered at the beginning of a performance. Through this slot a marble Hercules was discovered several years ago.After the Amphitheater, the wadi widens out and you soon come to the main city area, which covers about three square kilometers. Up on the right, carved into the rock of Jabal Khubtha, are the Royal Tombs. The first is the Urn Tomb, with its open terrace built over a double layer of vaults. The room inside measures 20 by 18 meters, and the patterns in the rock are striking. The Urn Tomb commands an impressive view and was once used as a church in Byzantine times. Next along is the Corinthian Tomb, allegedly a replica of Nero’s Golden Palace in Rome. Finally, the Palace Tomb is a three-story imitation of a Roman palace and one of the largest monuments in Petra. The tomb had to be completed by attaching preassembled stones to its upper left-hand corner. Around the corner to the right is the Mausoleum of Sextus Florentinius, a Roman administrator under Emperor Hadrian.

Continuing down the Siq, several restored columns mark the sides of the paved Roman colonnaded street. During the Roman era, columns lined the full length of the street, with markets and residences branching off on the sides. The slopes of the hills on either side are littered with the remains of the ancient city.

Along the colonnaded street you will see the ruins of the public fountain, or Nymphaeum. At the northwestern end of the colonnaded street is the triple-arched Temenos Gateway, which was originally fitted with wooden doors and marked the entrance into the courtyard, or "temenos", of the Qasr al-Bint. To the right of the Temenos Gateway, or Triumphal Arch, is the Temple of the Winged Lions. This was named after the carved lions that adorn the capitals of the columns. The temple was dedicated to the fertility goddess Atargatis, who was the partner to the main male god, Dushara.

Several hundred meters to the right of the street, near the Temple of the Winged Lions, is an immense Byzantine Church rich with mosaics. Each of the side aisles of Petra Church is paved with 70 square meters of remarkably preserved mosaics, depicting native as well as exotic or mythological animals, as well as personifications of the Seasons, Ocean, Earth and Wisdom. The church is thought to have been a major fifth- and sixth-century cathedral, throwing into question theories of Petra’s decline during this era. In December 1993, a cache of 152 papyrus scrolls in Byzantine Greek and possibly late Arabic were uncovered at the site. The scrolls, which constitute the largest group of written material from antiquity found in Jordan, are currently being deciphered and are yielding a wealth of information concerning the Byzantine period in the area. The Petra Church and its mosaics are currently being excavated and preserved.

Passing through the Temenos Gateway, one enters the piazza of the Qasr bint al-Faroun (in Arabic, "Palace of the Pharoah’s Daughter"

. This Nabatean construction dates from around 30 BCE, and is also known as the Temple of Dushara, after the god who was worshipped there. It was probably the main place of worship in Nabatean Petra, and it is the only freestanding structure in Petra. The Qasr was in use up until the Roman annexation, when it was burned. Earthquakes in the fourth and eighth centuries destroyed the remainder of the building.

. This Nabatean construction dates from around 30 BCE, and is also known as the Temple of Dushara, after the god who was worshipped there. It was probably the main place of worship in Nabatean Petra, and it is the only freestanding structure in Petra. The Qasr was in use up until the Roman annexation, when it was burned. Earthquakes in the fourth and eighth centuries destroyed the remainder of the building.Just beyond the Qasr al-Bint is the small massif of al-Habis. Steps lead up to the small, free museum which has a collection of artifacts found in Petra over the years.

The High Places

The High PlacesThe easiest of these climbs is up to the Crusader castle, or Citadel, on top of al-Habis. The steps leading to the top start from the base of the hill on the rise behind the Qasr Bint al-Faroun. The path goes all the way around al-Habis, revealing more caves on its western side. The entire round trip hike takes less than an hour.

"Al-Deir", the Monastery, Petra.

© Mouasher

From the Qasr, it takes around an hour to reach one of Petra’s most spectacular constructions, al-Deir ("The Monastery"

. To truly experience Petra’s immensity and power, a visit here is essential. The climb leads up the hillside, but the ancient path is easy to follow and not steep. Not far along the track, a sign points left to the Lion Tomb, set in a small gully. The two lions that give it its name can be seen facing each other at the base of the tomb.

. To truly experience Petra’s immensity and power, a visit here is essential. The climb leads up the hillside, but the ancient path is easy to follow and not steep. Not far along the track, a sign points left to the Lion Tomb, set in a small gully. The two lions that give it its name can be seen facing each other at the base of the tomb. The Monastery itself is similar in appearance to the Khazneh, but, at 50 meters wide and 45 meters tall, it is far bigger. Undertaken between the third century BCE and the first century CE, but never completed, it is less ornate than the Khazneh. The Monastery receives its name from crosses on the inside walls that suggest it was later used as a church. Al-Deir’s primary distinguishing feature is its crowning urn, which, unlike the Khazneh, is not backed against the rock. The urn can be reached via a series of ancient steps which connect the left of the facade with the rim of the urn. The views from on top are simply stunning.

Siq al-Bared, north of the popular Siq of Petra. © Ammar Khammash